Beer is revered in our culture. It is celebrated at festivals, idolized in cults, and consumed in rituals. It is the subject of adulation and the substance of myth. Beer is supernatural, like the gods of Olympus. Beer is…in a lot of trouble.

The trouble is, beer really has come to be regarded in our culture the way that Zeus and his bizarre family were regarded by the ancient Greeks. We do acknowledge that the analogy between beer and the Greek gods has at least one positive implication: to the ancients, the gods were a significant presence in daily life. BBJaze commends this because we believe that beer should play a significant role in our daily lives. But we also see a cautionary tale in this analogy.

While the gods were an integral part of daily life in ancient Greece, they were also objects of worship, which meant that they were a familiar presence but at the same time distant and mysterious, viewed with suspicion and fear. Alienation of this sort is a common effect of worship—and it seems to be what’s happening with beer in our own culture. The way that we celebrate beer these days more closely resembles idolatry than appreciation. Drinking beer doesn’t simply make us glad; it makes us ecstatic, like an electric eel in a tank full of light bulbs. We have come to believe that beer is other-worldly—something that mystifies rather than satisfies. This is why BBJaze cautions against the indiscriminate and self-contented celebration that has come to define the popular attitude toward beer in recent decades.

The problem really isn’t that we celebrate beer too often, but that we’ve made it too special.

Consider the following description of an IPA from a recent “beer-appreciation” event: A venerable and florid nose with overtones of jasmine and sawgrass, and a white, silky head. Is this describing a beverage or a retired gardener? This is no way to talk about beer. Now consider the following text from a 1905 Schlitz ad: When a patient is weak, the doctor says ‘Drink Beer.’ Now this is appropriate—and very revealing. For one, we see beer referred to in practical terms, as something that served a useful purpose. We also see that in 1905 cold remedies were much more fun than they are today. The point is that a century ago beer was a respected and valuable part of daily life. And this is how we believe that beer should be regarded today.

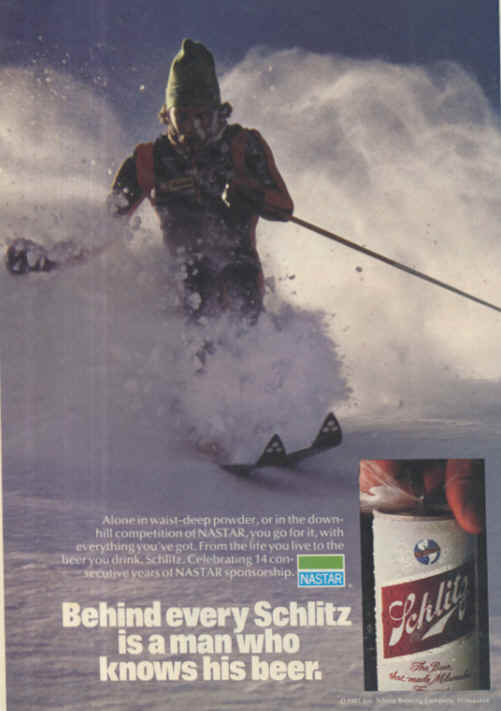

But it’s not. Several decades ago things began to go awry. In a 1981 Schlitz ad, we see an image of a cool-guy skier careening down a powdery mountainside, while the caption declares that Behind every Schlitz is a man who knows his beer. What is that supposed to mean? Are we to believe that this man is actually skiing behind a can of beer? The ad makes little sense. The only thing we know for certain is that from one Schlitz ad to the other we see a cultural shift in the way of thinking about beer from “drink beer and you’ll be well” to “drink beer and you’ll be cool.”

The advertising industry may be in part to blame, but that’s not the whole story. John P. Arnold’s landmark 1911 book, Origin and History of Beer and Brewing, was the first comprehensive historical study of the role of beer in human societies, and although it’s an informative and useful book, it also represents, albeit inadvertantly, the first tumble down the slippery slope that is our current predicament. Paradoxically, as the book sought to explore the role of beer in normal life, it plucked its subject from the realm of the normal and placed it in the realm of the “special,” presenting an everyday beverage as something worthy of inquiry and reflection. Nevertheless, Arnold’s book need not have led to the modern-day mystification of beer. In fact, it’s a substantial book that filled a significant void in historical studies. What’s largely to blame for our mis-appreciation of beer is our own frivolous, fame-obsessed, and sound bite-oriented culture.

Arnold’s book was a serious and detailed examination of beer history. Compare that with the gratuitous, decontextualized “information” BBJaze found during a recent web search: Noah had beer on the ark; Sumerian and Egyptian kings recorded beer recipes; Hammurabi wrote about beer in his “Code”; Confucius said, “An oppressive government is more to be feared than an tiger, or a beer”; Plato said, “He is wise man who invented beer”; Queen Victoria chimed in, too: “Give my people plenty of beer, good beer, and cheap beer, and you will have no revolution among them.” Gilgamesh drank beer! So did Ben Franklin…!

Of course, this information is intended to convey the idea that beer has been important to great civilizations. But what it really shows is the importance that our own culture places on being famous. Because we admire fame so much, beer fans simply like to see beer associated with famous people. For instance, if we were wondering about the role of beer in biblical times, we’re supposed to be satisfied by simply finding out that Noah had beer on the ark. Sadly, however, this tells us little about the meaning of beer in Noah’s world. If Noah took two of everything onto the ark—elephants, chipmunks, etc.—does that mean that he also took two beers? (If so, Noah grossly underestimated the duration of the flood.) We can conclude very little, but that doesn’t seem to bother us. We’re happy to have the myth that beer was onboard Noah’s ark. The fact that this information—this sound bite—conveys no real sense of history is satisfactory in a culture—our own—that has little interest in knowledge and meaning, and this coincides with the modern-day view of beer as famous, sexy, and special.

A serious investigation of beer history would reveal that beer has been universally significant not because it was special, but because it was most ordinary. Plato may have said “He was a wise man who invented beer,” but he probably announced this in the same way that he would say “Fetch my sandals.” (Plato’s information was wrong, anyway; it was a married man who invented beer.) As for Confucius, we admit that we don’t understand his point, but we won’t diss him because he has a really cool name and we’d like to see it make a comeback. (Wouldn’t you like to hear people say, “Confucius, hand me the remote” or “Confucius, we’re out of toilet paper”?) But we do understand Queen Victoria’s point. To her courtiers, she may have meant “make sure that everyone is too drunk to figure out that I’m not really in charge,” but the implication is clear: if the beer stops flowing, people will get angry. Beer was very much a part of daily life in Victorian times—so ordinary, in fact, that people would have been more likely to notice its absence than its presence.

In other words, what we really need to understand about beer is that it has traditionally been taken for granted. In using the phrase “taken for granted,” we don’t mean to suggest that people didn’t used to care about beer. The point is that people cared about beer the way they cared about air, as a natural part of their lives, as something so ordinary that it was invisible to them. Of course we know that air is literally invisible, unless you are in downtown Beijing or in a gym locker room, but we mean to make the point that air—like beer, traditionally—is so ubiquitous and essential in daily life that people simply expect to have it and are unmoved by its presence. When was the last time you heard someone say, “Boy I can’t wait until I get home from work so I can kick back and grab a noseful of O2”? In the same way, it would traditionally have seemed strange for someone to make beer seem so exquisite and special. Beer was not so much a reward for a workday completed as a constant and indispensable companion during the workday itself.

In today’s world, we tend to notice when beer is present, not absent, because we expect it to be absent. So when it is present, we hoot and holler or we ogle and drool. The disappearance of beer from daily life has infantilized us. That’s because in limiting the role of beer in daily life, we’re defying thousands of years of civilized behavior, and we’re denying our instincts. Unfortunately, denying our instincts is largely what our politically correct culture demands of us. This is not to say that all politically correct behavior is unwelcome, but somehow casually drinking beer throughout the day was perversely grouped together with genuinely disturbing activities, such as hitting on your friend’s grandmother. Why, really, has drinking beer become unacceptable as a part of the daily routine? We don’t know, but we hope that historians of the future will someday view this as a remarkable cultural and historical aberration—and will deliver lectures about it while drinking beer.

We must recognize the danger of marginalizing beer, of removing it from the public square and relegating it to the sphere of leisure and recreation and “specialness.” What’s at stake is the very survival of beer itself. In the developed world, which is where we at BBJaze like to believe we live, beer consumption has been on the decline for decades, and that trend will only accelerate unless beer drinkers take back the public square. Those among you who will say that beer appreciation events, like tastings and festivals, are doing precisely this are mistaken. Such events, by themselves, have the opposite effect insofar as they reinforce the idea of beer as something rather unordinary, as a curiosity to be celebrated and revered. Such events monumentalize beer. And when something is monumentalized, it means it has become peculiar and old-fashioned.

Do we want our grandchildren to one day find themselves visiting the National Beer Monument in Washington D.C., standing before a 12 foot-tall bronze cast of a beer can and a marble sculpture of a fat abdomen, reading about how beer had once been instrumental in the development of the civilized world? Certainly not. Beer must be de-monumentalized. It must be taken for granted. It must become so ordinary that we fail even to notice it. It must be forgotten in order to be fully appreciated.

Here’s the point, ultimately, that we want to make about beer: Drink it, don’t think it.

How’s that for a sound bite?